top of page

3.1. Spinal Nerves

Spinal Nerves

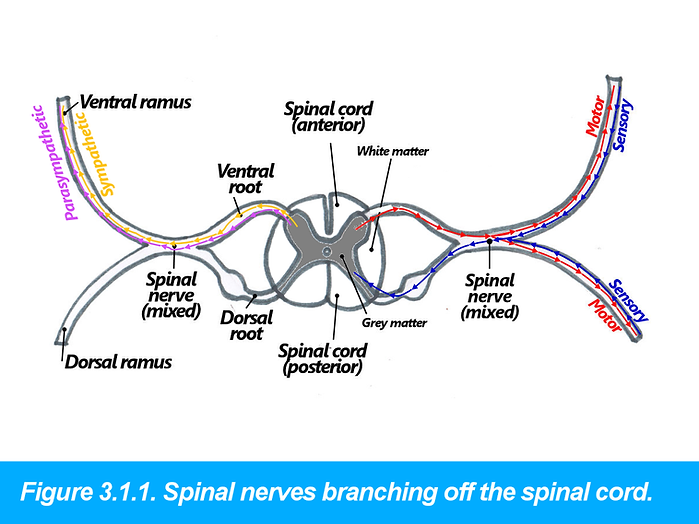

Let’s begin by looking at spinal nerves, and defining what they are. A spinal nerve is formed by the sensory and motor neurons that enter and leave the spinal cord. These neurons are part of the somatic nervous system, but neurons from the autonomic nervous system can also travel in spinal nerves (the autonomic nervous system is essentially made up of the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions – more on this later). Every spinal nerve is associated with a dermatome and a myotome (see below for more info).

Consider the following example at the vertebral level of T3. There are sensory neurons coming from the upper chest, carrying information like touch, pressure and temperature, and eventually these neurons travel together in a close bundle called the ventral (or anterior) 'ramus'. The nerves coming from the back eventually travel together in the dorsal (or posterior) ramus. These two 'rami' eventually join together and are then called a 'spinal nerve'. The spinal nerve then divides again and the sensory neurons enter the spinal cord via the dorsal root. Processing occurs in the spinal cord/brain. Motor fibres then leave the spinal cord via the ventral root. They also enter the spinal nerve and are then distributed via the dorsal and ventral rami. Sound confusing? Put simply, a spinal nerve is formed shortly after neurons enter/leave the spinal, and a spinal nerve can have sensory, motor and autonomic neurons inside it. Take a look at the Figure 3.1.1 for more info.

Consider the following example at the vertebral level of T3. There are sensory neurons coming from the upper chest, carrying information like touch, pressure and temperature, and eventually these neurons travel together in a close bundle called the ventral (or anterior) 'ramus'. The nerves coming from the back eventually travel together in the dorsal (or posterior) ramus. These two 'rami' eventually join together and are then called a 'spinal nerve'. The spinal nerve then divides again and the sensory neurons enter the spinal cord via the dorsal root. Processing occurs in the spinal cord/brain. Motor fibres then leave the spinal cord via the ventral root. They also enter the spinal nerve and are then distributed via the dorsal and ventral rami. Sound confusing? Put simply, a spinal nerve is formed shortly after neurons enter/leave the spinal, and a spinal nerve can have sensory, motor and autonomic neurons inside it. Take a look at the Figure 3.1.1 for more info.

Spinal Segments

A spinal segment is an area of the spinal cord proper that gives rise to two spinal nerves. For example, the T3 spinal segment gives rise to two spinal nerves that will provide sensory innervation to a band of skin on the chest and motor innervation to the third intercostal muscles (these muscles that lie in-between the ribs). The spinal nerves might also contain autonomic fibres. It is important to realise that spinal nerves and their branches provide sensory and motor innervation to skin and muscles that are far away. For example, the lumbar and sacral spinal segments will give rise to spinal nerves that provide innervation as far down as the feet.

Dermatomes and Myotomes

As has already been alluded to, a dermatome is the area of skin supplied by a single spinal segment and its associated spinal nerve. For example, the T10 dermatome extends horizontally around the abdomen, from front-to-back, at the level of the umbilicus. All of the skin in this region, which is about 1 inch in height, conveys its sensory information to the brain via the spinal nerves of the T10 spinal segment.

A myotome is the group of muscles that is innervated by the spinal nerve of a spinal segment. For example, the myotome of the C5 spinal segment/spinal nerve includes the muscles of the upper arm (biceps brachii, shoulder region (deltoid, infraspinatus, supraspinatus) and the forearm (brachioradialis). It’s important to realise that, in this example, although these muscles are part of the C5 myotome, some are also part of the C6 myotome – C5 and C6 together form the musculocutaneous nerve which supplies the muscles of the upper arm.

A myotome is the group of muscles that is innervated by the spinal nerve of a spinal segment. For example, the myotome of the C5 spinal segment/spinal nerve includes the muscles of the upper arm (biceps brachii, shoulder region (deltoid, infraspinatus, supraspinatus) and the forearm (brachioradialis). It’s important to realise that, in this example, although these muscles are part of the C5 myotome, some are also part of the C6 myotome – C5 and C6 together form the musculocutaneous nerve which supplies the muscles of the upper arm.

Clinical Top Tip:

Cord Damage

As was mentioned in a previous Clinical Note, the effects of spinal cord damage is dependent on the location of the damage.If the spinal cord is damaged at, say, C5, the C5 spinal segment and all those segments below it will be affected.This means that dermatomes and myotomes will also not function properly. If a myotome cannot function at all, the individual will not be able to move their muscles. If a dermatome cannot function properly, the individual will not be able to sense anything from that area. Note that the C3, C4 and C5 spinal segment are responsible for breathing (because they give rise to the phrenic nerve that supplies the muscular diaphragm). Breathing will be severely affected if these spinal segments are damaged.

Related Video

Related Video

bottom of page